“Hey Daniel, how are you?” “Okay, coach, you know… taking it day by day.”

“Why the long face, is it about yesterday’s game?” “Yeah, he didn’t let me play again… he said I’m not “bad” enough and that he can’t use me against such a strong team and that maybe in the next game I’ll get in if the week goes well.”

Here is a summary of my conversation with that kid, who in his struggle represents many of us in the world of team sports—the fascinating and challenging relationship with the head coach.

As an external and intimate part of the competitive athlete’s life, I get to closely examine team politics. Your successes, your benchings, the coach’s shouts and criticisms, the “educational” punishments, the amazing successes one week that turn into real defeats the next—like a wild roller coaster ride full of twists and turns that travels through a dark cave, where we have no idea if the ride is broken or if this is what the manufacturer intended.

Outside the competitive season, I get to hear about experiences in teams: where you were thrown out in disgrace, where you were accepted with threats, and where you were welcomed with enthusiasm and promises that “with me you’ll play.”

In most cases, I will of course only hear the athlete’s side, who usually prefers their own story over the coach’s perspective, who often cannot explain himself in depth to every player due to the workload.

“I definitely deserved to start this week, I don’t know what happened and what can be done to fix it, and the coach wasn’t clear,” a young fox told me.

It seems that this situation, of “punishment” connected to a lack of clear understanding of the steps needed to fix the problem for the following week, is very painful in the heart of every athlete seeking excellence in sport.

Usually, head coaches will defend their decision to bench you or cut you from teams with statements like:

- “You’re lacking the killer instinct, you’re too nice of a kid.”

- “You lack coordination, strength, and speed compared to others. I want you to work on that.”

- “Your game wisdom is lacking and you don’t yet have the body language of a player who deserves to start for me.”

- “Listen, there are some good players in your position…”

- “Come and start, there’s no money right now, and we’ll see mid-season how we can progress.”

- “We’re already 25 players in training, it’s becoming too much…”

These and similar statements are very general, although still correct from the coach’s perspective—we shouldn’t criticize the simplicity of the phrasing at all but rather take a step back and decipher why a random person who knows a thing or two about the game said this to us, and create an independent process that will nullify the decree not through politics, but through actual deeds.

Indeed, not everyone will like you and not everyone will connect with you as a person, let alone as a soccer player—but soccer coaches are not something you can usually choose—and part of the art of self-improvement (the process of becoming a complete athlete) is also getting along in professional relationships as much as possible from the position of the employed—in other words, an employee in a soccer team.

Just as it is impossible and incorrect to tell a child who is 1.78 meters tall that he will never be a basketball player because of his height (as this is not within his control), it is also not right to attribute our success to arguments like “the coach hates me” or “I have a black curse because I accidentally walked under a sign” or even “they brought players in my position, I’ll never succeed here” because these are the things that are beyond your control to change, and all that’s left is to fall into bitterness for another eight unfun months of wasted time and tears before bed.

In this article, we will outline guidelines not only to correct existing general criticisms from your coaches but more importantly, to create a first impression of an elite athlete that is hard to ignore, an athlete who enters the coach’s heart in such a way that the coach will overlook his shortcomings and focus on his strengths every day, truly believing in his success in the team and standing up to defend him in professional staff meetings.

“I’m not at fault, it’s the coach.”

First, we need to address the eternal question: What if it really is the coach’s fault? What if I did everything right, but he just doesn’t like me because another player’s dad brought him lunch from the restaurant he runs, and that player has become his favorite?

Just because there are accidents on the roads from time to time, does that mean we should avoid using cars? In other words, the fact that there are biases shouldn’t prevent us from doing everything within our control to change the coach’s opinion. After all, switching teams isn’t easy and it’s not a healthy habit in the long run. It would be beneficial for the athlete to go through all the points in this article and more, to become the best player they can be and, in the process, get used to situations where even that might not be enough.

Therefore, they will need to find ways to soften the hearts of the “most unfair” rather than showing constant resistance that won’t improve the athlete’s political standing.

The justice-minded among you might say that this still doesn’t solve the problem in the industry, that there are many unqualified coaches and a lot of real biases, etc.—and you’re right, it is truly disappointing to work on yourself physically and mentally while the person in charge of your professional future is full of internal corruption and flawed values. But on the other hand, you can’t go about fixing the world while being an active player—that would corrupt the competitive spirit. You can deal with these issues in the second phase of your professional career, from the sidelines or in offices—but not in the real-time pursuit of your dreams.

We can even go so far as to say that most coaches will be “blind” to your efforts and might even be toxic towards them. How many times have I heard comments like, “All your fitness training and low-fat yogurts you eat in the locker room, and for what? So you can make such a terrible pass?” In other words, a cynical use of the athlete’s professional lifestyle against him, as if fitness training were an insurance policy against making mistakes in the game.

In such a corrosive atmosphere, the athlete often has to operate, but allow me to be the advocate for a moment for such a disturbing phrase from the coach.

I don’t truly believe that the coach thinks, “All your work is in vain if you made such a pass.” Rather, he is trying to express a higher idea—the notion that the game is random and one must step out of the sometimes off-putting “framing” of an athlete who performs external units and only eats according to a strict diet.

In the previous article, “Developing Personal Style,” we saw that the “earth” approach—when overly expressed in the locker room—can cause some aversion towards you due to the inherent mismatch between the random game of improvisations and quick reactions and the expectations set by a nutrition plan.

In the following sections, I ask you to get into the mindset of how you can indeed impress coaches, whether good or bad, without succumbing to the syndrome of the lowered head in the locker room—those players who are sometimes seen isolated with headphones before a game, with the romantic notion that the bitterness they have entered will touch the coach’s heart, who in turn will shed a tear over an old picture of himself playing soccer with his son at the age of 4, and then go into a trance of emotions that will end with him giving you the keys to lead the team forever.

From the Perspective of Coach David Berman

Not from the team, not from the dressing room, and not from the coach. “I tear the floor, it’s a short name and plays before.” This sentence is probably the most football talk. Coaches in Israel almost always prefer players who promote them in numbers rather than athletes, because that is the trend in our profession in Israel. An average coach is replaced every 5.6 months and in order to maintain his position for a longer period of time he will go with what helps him now.

Today’s knowledge is available on the table for everyone – both coaches and players. Coaches need to learn, develop, and grow just as players do. Learning is endless, but the biggest gap is in human management. From the coach’s side to manage 20 and a few players, to try to see the point of view of the person in front of him through his eyes, but with a deep understanding of the coach about his way and where he wants and sees the player integrated into this way in clear words and constant feedback to the best of his ability.

From the player’s point of view, he needs to know how to handle his coach. To be open to criticism, to come without ego and try to understand exactly what the coach wants and needs from him and then to aim for it and try to be the best in it.

To players, I say, don’t be afraid of the coach. Talk to him, consult with him, want to get feedback even if it’s bad and unpleasant. Know how to process the information cleanly, not judgmental and blaming neither the coach nor you as a player and human. Only from a clean place can progress be made in this relationship system. After all, the one standing between you and your dream is the coach. Learn to speak with them, manage and act against them.

The coach is a single person, mostly against everyone. They raise him when he succeeds and lower him when he fails and mostly in football the odds are always against you, so more lower than raise. So give the coach a feeling that you appreciate and see him, as you would like the coach to see you. It’s not a surefire recipe, but it will miraculously improve your chances of managing the coach more humanely.

General body language – eye contact, neck posture and walking style

First, let’s talk about the overall physical appearance towards the world and other people – especially concerning stability, eye contact, and the way you walk or sit.

Even before we delve into athletic action itself, which in itself reveals a lot about your unique inner world – your visible shadow has a very real impact on the way people interact with you.

Identical twins at the same athletic level may approach a coach, one receiving a “hey, what’s up, champ?” and the other receiving a “yes, how can I help?” – and it’s not because of the coach’s bias but rather trivial matters such as the way you walk, stand, and look at them.

Coaches very much appreciate a high posture, with a centered center. They like it when you look at them when you turn to them and like it when you walk like this on the field and in the dressing room with other players.

Any neck lowering for no reason, such as checking a message on your mobile, requiring a collapse a did head and even Sad entered type does The that category least “Strong. there Please sense is not or judgements show sensitive express way use cover beloved ones stay physically strong results first stop begin start serve purpose significant must assists

We need to understand that these are not things that consciously act on people – meaning it’s not like a coach will look at you and write in his notebook, ‘Today I saw Dvir walking with a proud head.’ Instead, it’s about your overall energy being higher in such a way that the coach feels good that you’re there – he feels that you contribute to the competitive atmosphere and team cohesion, actively taking part in the battle and victory. In fact, it might be guessed that behind his secret thoughts a sentence like ‘I’m glad Dvir came to practice, everyone else here seems caught up in themselves, and he makes me feel like I’m not wasting time’ would pop up.

The nature of the action – sharp and aggressive or lazy and submissive?

After we’ve understood why your first impression is so terrible, we can talk a bit more specifically about the first impression as it manifests on the field, in real actions.

Of course, this includes the athletic technical aspect that we work so hard on – but even before working hard on the mechanical aspect, there are mental foundations of an “athletic approach” that need to be laid on the table and can make you more dangerous players starting tomorrow.

Every athlete at Red Fox learns a number of such principles in his first training sessions, as it does not depend on technique but on will. For example:

A. Always try to be in a position from which you can respond to sudden danger. Such a position shows that you are ready for any scenario, that you respect the training, and regardless, makes you more dangerous in the eyes of the opponent.

A coach who sees a player standing with fully extended knees while there is operational activity nearby immediately thinks, “You look like you don’t really care about the game” – and rightly so! A player who is not in an athletic position for most of the game is likely here for the hobby and waiting for it to end so they can go home to play FIFA, not for serious training and career development. Personally, I would not actively try to develop a player with such body behavior but would invest in those who seem more “serious” to me.

Try to treat the ground like a snake and scorpion-infested terrain in your activities. The grass or field should be a place “to lift your foot sharply to avoid stinging,” not “to give it strength” as many players wrongly perceive it, which makes them appear unnecessarily heavy.

When a coach notices heavy forces plunging everyone into the ground instead of staying above it, immediate associations of heaviness, laziness, and excess weight arise. Not always does the coach know what the root of the problem is, but in a team of 20 players, it’s very rare for such a coach to invest significant time in a player displaying these associations.

With athletic training, everyone progresses at different levels and with varying capacities, but undoubtedly, everyone can relatively improve their appearance and agility today just through sheer will.

Demonstrate movement ranges wherever possible – behave like a cheetah, not like a mouse.

During sprints, change of direction, explorations, kicks, and strikes – guide your will to seek ranges. Undoubtedly, players who feel comfortable showcasing their movement ranges are immediately linked by the coach to live prey, unlike those who live in fear of slipping every moment. Presenting movement ranges is linked to psychomotor comfort with your body and positioning yourself as a predator before yourself and your surroundings. A person who feels comfortable in their body moves their arms while walking and displays an upright chest. A person who is uncomfortable with their body will be hunched, with hands close to their body and small steps, attempting to hide their existence from the world and evade criticism through a type of sophisticated defense mechanism, which simply repels as implied.

Show the coach that you are comfortable in your body, if not for the performance, then for the impression you convey towards him.

The foxes train with “will” behind presenting the ranges from the very first lesson.

These principles are distinct athletic components that require extensive technical training over time. The text is not implying that “it’s all in the mind” when it comes to them, and that the training process is purely mental – not at all. Rather, it suggests that movement should stem from an early willingness learned in the initial lessons, not from following the coach’s instructions. Therefore, you can improve these three points starting tomorrow, in one way or another, to enhance your standing.

Here’s the translation:

Dedication, discipline, and manners – looking beyond the “self”.

If there’s one thing that drives coaches away from players more than anything else, it’s the player’s obsessive self-attachment. Constant discussions about “what about me, when will they listen to me, when will they notice me,” and the associated body language may stem from good intentions, but to a coach juggling 25 students, it signifies that you’re not a team player. Every time you succeed, you take all the credit for yourself, just as you only focused on yourself when things weren’t going well all year.

To land on the coach’s good side, start working on basic gestures like a “good morning” or “thanks for the training, have a great day.” More handshakes with eye contact, more “okay, I’ll do it” with a determined look, instead of quietly receiving instructions with your head down.

When you help with equipment, do it with love and humor.

When you’re alone with the coach and have the opportunity for casual conversation, ask about the team, upcoming games, and how he thinks the team is doing compared to “how I would have been.” Inquire if there’s anything you could focus on improving in that session.

Regarding your interaction with the support staff, whether it’s the physiotherapist, field manager, equipment manager, or assistant coaches, show general interest without becoming personal advisors on emotional matters. When you want to contribute or simply hear from the team in general, they will approach you personally out of affection. Therefore, approach them with courtesy and curiosity, and you’ll receive personal attention in return, not the other way around.

In dealing with other players, maintain a stance that is “tough but fair.” Don’t allow anyone to step on you or disrespect you in the locker room or on the field, but also ensure you treat others fairly and avoid doing the same to them. This is the only way to lead by example.

In general, politeness and manners are not substitutes for competitiveness and justice, but rather a constant desire for fairness. Sometimes, justice requires being firm. Approach every situation as a living organism that changes constantly, rather than robots who say the same “good morning” mechanically every day. This is not the aim of politeness and manners.

If the coach sees that you know how to stand up for yourself when someone brings you down or supports a teammate when another player criticizes them, all while maintaining politeness and manners, you’ll appear as leaders of the team, akin to champions of fairness. Anyone can be problematic with ego-driven sandals, and anyone can be courteous and kind with three pleasantries during training—but it’s the combination of both that is rare in locker rooms. Without this combination, you won’t achieve anything.

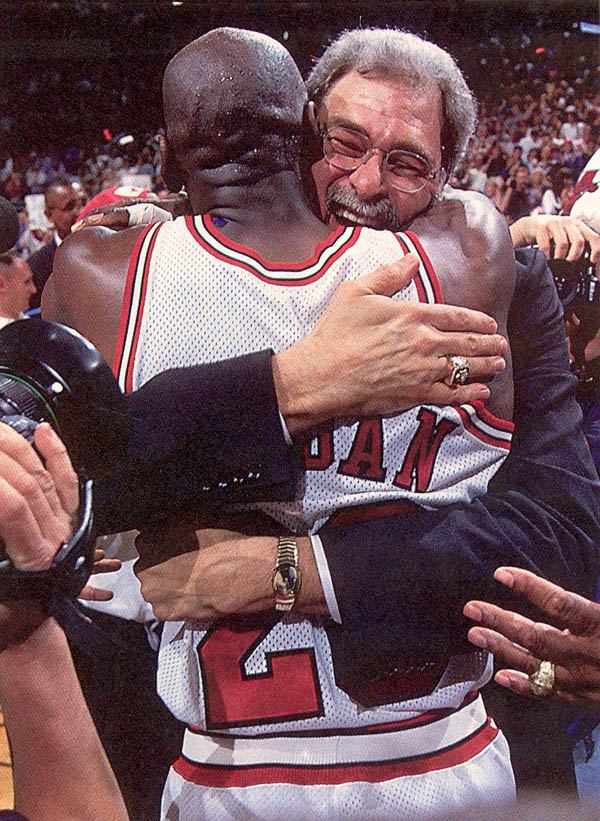

Phil Jackson, the legendary coach of Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls, often emphasized to Jordan the concept of “tough but fair” in countless opportunities. Jordan consistently bought into it with his intensity. Jackson knew how to lift players up while also challenging them. He demanded the perfection he expected from himself and his teammates. In essence, Jackson would tell Phil in his actions something like “You have to trust me, and I won’t let you down, I promise”—this is how to approach your relationship with the coach.

The difference between a “great kid” and “goodie two shoes”

In one of my junior high school graduation certificates, the teacher wrote as a comment, “Ofir is a good kid with high potential.” That same evening, I glanced at my good friend’s certificate and saw it read, “Yotam is a lifeblood in the class,” and I wondered about the difference, because being a lifeblood in the class necessarily implies being a good kid, but being a good kid doesn’t necessarily mean being a lifeblood.

As life went on, I learned that being a “good kid with potential” meant there wasn’t enough influence on the environment to get people in the area of your brain that they want to be around you. “A good kid with potential” is like saying that the week old Deli Roll at the city center place isn’t disgusting. Does the fact that the food is eaten and not repulsive satisfy the restaurant owner?

This is a direct continuation of the previous paragraphs, because if we are fully committed to “goodwill” style, our friend will conquer the team, and the coach will immediately notice that it is counterfeit and that you are not really biting or knowing how to stand on your own.

The only real goodwill is the one that made a difference in the world. I’ll give you an example:

To the question “How are you?” you can answer “Good, thank you” and be considered a polite child. A good kid with potential. But you can also answer “Better than yesterday, and how about you?” – even to people you don’t know at all – something that will take you from being a good child to being an interesting child.

On the playground – a good kid with potential will refrain from demanding things from their teammates on the team, claiming it is “not nice and not respectful” – while an interesting child knew how to demand certain moves or a certain relationship.

A good kid with potential will help return equipment at the end of training, but an interesting child will check that everyone else has done their job and hasn’t forgotten anything on the field.

A good kid with potential will apologize for things they didn’t do, while an interesting child will ask where exactly their mistake was.

No one appreciates 1 week old shawarma, just as no one appreciates a crappy, stubborn, arrogant child who only thinks of himself with exaggerated confidence – so don’t be an exaggerated character here or there, but find yourself in search of the middle ground (which by its very definition, as a middle ground between two animal extremes, will never be fully achieved).

Understanding that the coach also wants to advance and succeed, and that he too could be replaced, just like you.

Sometimes in my initial interview with an athlete, I ask the oldest question in the book, “What is your dream? Where do you want to go?”

Once, one of them, an amazing 11-year-old athlete no less – returned the question right back at me.

After a brief pause of nearly 3 seconds on the clock, I stepped out of my coach shoes for a moment so I could give him an honest answer.

“I want to become a speed coach in the Premier League,” I told him. At this point, I metaphorically laced up my coaching shoes again with nimble hands and continued: “We have a mutual responsibility – for me to progress, I must do everything to help you achieve your goals, and for you to reach your goals, you need to support me.” In other words, our connection is not just professional; my entire future depends on that athlete because his success is my ticket forward, and nothing else.

The athlete enjoyed this with satisfaction, glancing briefly downward as if acknowledging the mutual responsibility I had just laid before him.

We’re accustomed to seeing coaches as authoritative figures who have already achieved everything they wanted in life, and all that’s left for them is to go to work and try to win games for honor or for the old passion for the game that has been preserved since their youth, but that’s often not the case.

Most coaches you encounter in your life will engage in their profession day in and day out in one way or another, and they’ll need to answer to team managers and professional administrators regularly in order to advance or get better terms.

If we only understand that most of a coach’s decisions are made with a systemic consideration of “what will be in the future and what will the bosses say,” we can truly step out of the student’s shoes and actively participate in shaping the coach’s future.

Never thought you’d hear a sentence like that, huh? That you, with your size 38 stuck shoes and trendy haircut from a nearby barber shop, would take part in the future of the great and scary coach? Well, that’s exactly it.

The moment we realize that the coach’s entire resume depends on the performances of their students – we can understand these points more deeply – we can base all our efforts day in and day out on the team with the knowledge that there is mutual responsibility here, not just “opportunity seizing” – a dismissive term I hear all the time, as if you exist only to seize an opportunity from someone.

On the contrary, you need to provide the coach with the opportunity to defend you in a board meeting, the opportunity to proudly speak about you with their family during vacations, and in order to do that, you need to first take responsibility for them.

sense of humor

“To truly laugh, you must be able to take your pain and play with it.”

Charlie Chaplin

Psychologists agree that individuals with a developed sense of humor are often more receptive to therapy. This is because they can take a step back from themselves and play with their problems in a humorous way. This approach can lead to faster therapeutic progress compared to someone who views their life in a more existential and anxious manner.

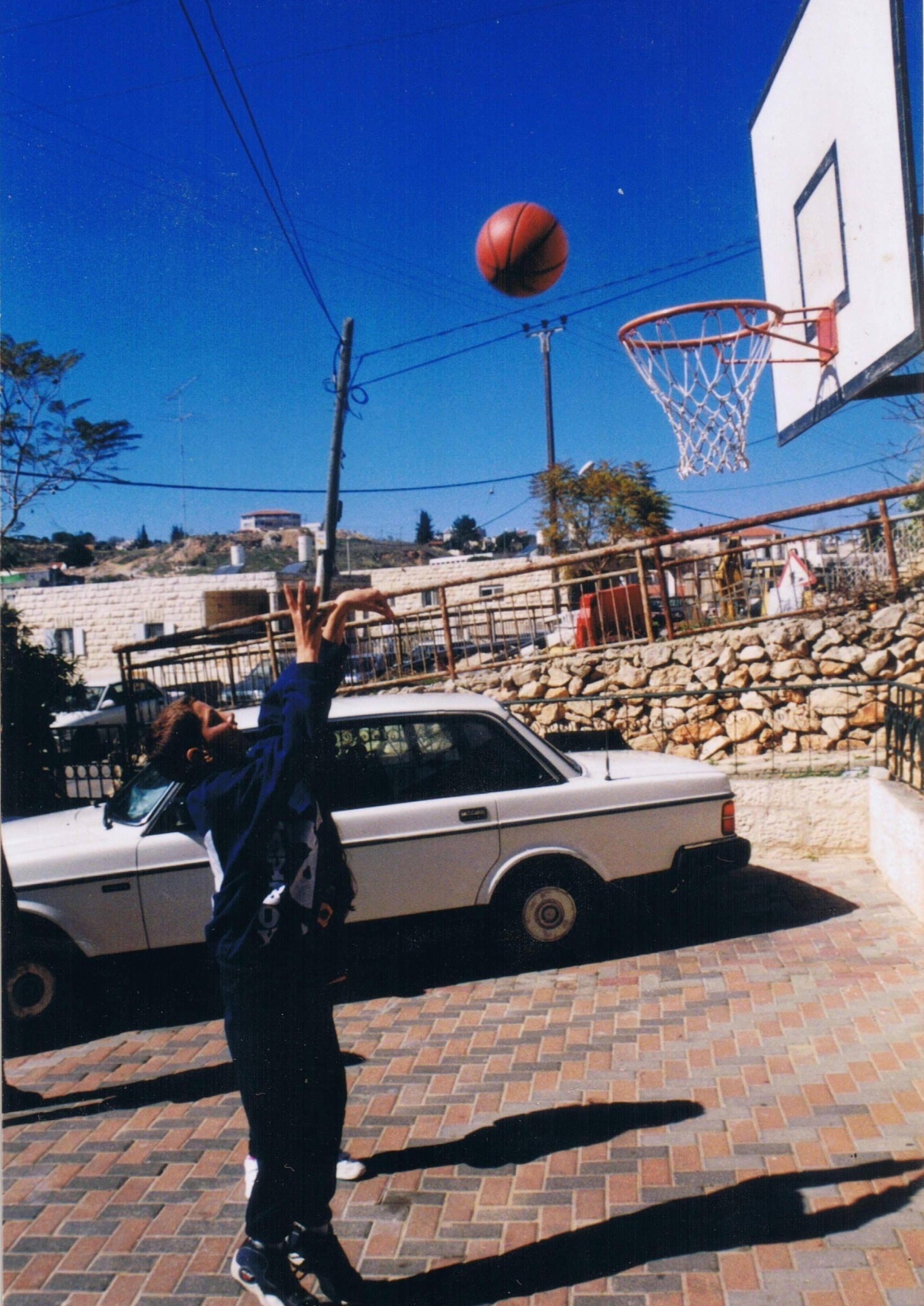

I remember when I was really young, about 20 minutes before a Monday afternoon basketball practice at the Pis Center in the neighborhood. I organized a game where myself and 3 friends competed to see who could make the ugliest shot among us, while the other kids who arrived early would be the judges.

When it was my turn, I threw the ugliest shot imaginable – all my joints were crooked, the ball left my hand with a brutal lack of sensitivity, hit the clock above the hoop hard – bouncing several times above the ring with terrible metallic sounds, and finally went into the net.

Amidst everyone’s laughter, from the corner of my eye, I caught Coach Marvi looking at me, smiling genuinely while shaking his head from side to side over my act before he headed to the front desk. “Ophir Levi, a dinosaur like you,” he said in his distinctive accent, and continued with his duties at the counter. “He probably thinks I’m such a fool,” I thought to myself with a half-smile, but I’ll take Marvi’s half-smile, a coach I admired every day despite his anonymity.

The day I understand that I showed him that I am not just a technique machine, but through humor – I showed that I understand deep things about basketball, things that cannot be put into words in the same way you can’t understand why we loved a certain song more than another.

It was a moment when I saw Merabi the human. I saw this head teacher whose everything is as organized as the hairpin of the most organized girl in the class in September – smiling and turning red. A connection was formed between us that lasted for years after.

And to you, Merabi- if you ever read these comments – I met you at the age of 10 and today, over 20 years later, your memory still has a great impact on my life. I love you coach.

Extracurricular Activity

An athlete can innocently create a connection with their coach through extracurricular activities like clubs, fitness training, or technique sessions.

Those sideline coaches sometimes echo the athlete’s efforts to the head coach, thereby singling them out as someone who goes the extra mile after their dream, if it truly comes from them and not from their parents or other external influence.

Head coaches typically have to manage the “big dream” of about 20 individuals per training unit. This is practically impossible, so they employ a pyramid system where children who “ask for more” receive one more degree of consultation.

When an athlete performs extracurricular activities with enthusiasm, they essentially tell the coach, “I want to do more than others; I want to go an extra mile, throw me another bone” – something a fair coach usually does if it comes from the heart.

When a coach knows they are not the sole responsible party for your future, they feel more comfortable being direct with you and “playing” with your status left and right. This is essentially the “bone” they give to those who prove themselves worthy of more, because they cannot guarantee minutes or advancements, but they can ensure that their supervisory eye is on you. This leads to them noticing early on when it is indeed your time to play.

Healthy independence from parents

If there’s one thing every coach hates in their profession, it’s the relentless and demanding involvement of parents in sports. 25 mothers and fathers on constant phone calls, endlessly explaining why this and why that, and engineering a suitable explanation that satisfies each parent doesn’t seem achievable even with artificial intelligence. Therefore, it becomes a heavy emotional burden on the working coach.

As a young person aged 12-20, try to demonstrate independence to the coach whenever possible. Don’t complain to your parents every time they pull you out because all they’ll do is feel your pain and try to negotiate with the coach to secure more playing time. It’s not wrong of them fundamentally, but this should be reserved for extreme cases where all the discussed clauses apply through effort and external assistance is still needed.

Your parents ultimately want what’s best for you, so it’s your role to show optimism even on bad days. Parents love to feel that you’re on the right path more than they love you playing and winning, so as long as you demonstrate determination and a willingness to improve, they generally avoid talking to the coach. When you feel it’s not enough, your wise parents will talk to the coach.

Today, good coaches schedule planned meetings with parents to ensure that every child receives the attention they deserve, discussing areas for improvement and acknowledging progress since the last meeting.

Numbers

Up until now, everything was so romantic. If only we could stay in this beautiful movie and live in happiness and wealth until the good ending separates us. But the truth is, just as fresh pastries satisfy the sweet tooth – statistics tell the tale and buy the coach’s heart

Amidst all the general principles, let us not forget the primary goal of a professional player in a mature team (the ultimate goal of most young athletes) – to provide relevant statistical measures that are supposed to lead to the team’s success

If so, one can consider all the principles presented in this article as opportunities to showcase statistics, which is the ultimate goal. That is to say, if we’re talking about an excellent, independent kid with good body language and superior leadership qualities, they will receive more opportunities in the season to demonstrate their ability to provide statistics than if they lacked these qualities. Indeed, this sometimes means that a talented player who doesn’t meet any criteria in this article except for delivering statistics will still earn appreciation from the Israeli coach – just as Coach Barman stated above. However, I suppose these are just the ways of the world.

This shouldn’t disappoint us because we’ve said that we’re only dealing with the cards dealt to us from birth or until we’ve awakened enough to seek self-improvement, like the readers of this article. There is no higher purpose in sports, and any bitterness about what was, as correct as it may be, is completely irrelevant to the discussion.

So, lift your head from the ground because you’re not working in a holy society as a gravedigger. There’s much to do before you earn the right to self-mercy – and the earlier you start, the more beloved you’ll be by more coaches.

“Ofir, not everyone will love you in life,” Mom said, and she was right. And while there’s no need to beg our haters to love us (definitely not) – when it comes to the professional side, I hope this article provided you with some of the “secrets” of players beloved by coaches in Israel and around the world. We’ll continue discussing more ideas in Part Two soon.