Our foxes have returned from their vacations, and with the summer training, the query continues.

In “Foxes Ask #2,” we will answer 3 more burning questions that arise early in the training program.

Why is there an endurance component even though the sport I engage in (goalkeeping, volleyball, football line) statistically does not require much endurance?

It’s essentially the same as asking, “If I play with a ball, why do athletic training sessions take place without the ball?” In other words, the nature of the questioner is to seek absolute specificity in all his actions, but the perceptive questioner surely forgets an important fact: if specificity is the key to all improvement, why not simply play the sport more often? After all, there is nothing more specific than the sport itself.

The answer, of course, is that this is not how things work. Since it is impossible to improve components without “dissecting” them—removing them from the whole before reassembling them later—it is impossible to train one component without touching on another. Let’s explain:

It is well known that behind every motor action that is performed more easily, there must be thousands of hours of training or thousands of repetitions that caused the neural pathways responsible for the complexity of that movement to be saturated with signals and developed enough to function independently of the brain’s long-duration processing centers.

In musical instruments, for example, any decent musician can “learn” the notes of any song within less than an hour, but to play that song effortlessly during a performance requires many hours of saturating the neuromotor system, which initially seems contradictory to the very ability to learn the notes.

In athletics, it is similar. On the one hand, we have scientific principles in the form of energy reserves “lacking chemical or cardio-respiratory endurance” suitable for volleyball, football, high jump, or a 100-meter sprint. On the other hand, there is the undeniable need for the athlete to perform enough volume in those “endurance-lacking” movements to lead to profound neural changes.

“Endurance Fitness” versus “Work Volume Fitness”

It can already be seen that in order for that “pure endurance component” to be properly instilled in the heart and soul of the athlete, we must lean towards “endurance” or, more accurately, “work volume fitness.”

Work volume fitness is essentially the ability of an athlete to perform the required training in sufficient quantity to lead to profound neuromotor improvement, not just the acquisition of knowledge about the action.

For example, it is possible to teach the technique of jumping from two feet in about half an hour of talking and demonstrations with breaks of about 2 minutes between maximal demonstrations, as science “requires.” However, every jumper knows that in order to jump naturally on a regular and reliable basis (minimizing “bad days” in performance), it is necessary to perform very high volumes of jumps, often far beyond what kinesiological science has researched as “recommended.”

It is known that Olympic 100-meter runners train a lot in the 300 and 400-meter ranges, distances that require completely different chemical components than the 100 meters from which they make their living. So why? Why not focus on 20 to 120 meters to stay specific?

And this is to create the ability to endure specific training more easily without reaching overtraining, thereby leading to motor improvements similar to musical instruments.

A goalkeeper, for example, needs to create an optimal state where his neural response to visual stimuli is accompanied by an appropriate athletic movement ability. This is similar to an MMA fighter who needs to respond correctly to stimuli beyond his control. If that fighter were to train in a “specific” manner, the sports scientist would tell him to perform sets of 6 dodges from punches, rest for 5 minutes, and do this twice a week to avoid “overtraining.”

But Kung Fu fighters in monasteries perform thousands of repetitions a day, in various forms and intensities, to create effortless playing from the musical instrument called the human body.

And similarly, a goalkeeper will need the capacity to perform specific training thousands of times without reaching overtraining. Moreover, since when did we start succumbing to overtraining? Who said it is impossible to train the ability to avoid overtraining? We only hear about workloads and how no one should exceed them. Since when have we, as coaches, become so defeatist? Where have we failed in our understanding of the human body that we don’t believe it is possible to train the ability to avoid overtraining by building work volume?

Of course, there are also chemical reasons why training over a longer distance might lead to delaying the slowdown in the shorter distance, but this proves the same point—there is no such thing as truly “specific training.” It is a defeatist term that aims to strip any significance from the artistic sophistication in training programs, a kind of ideological fascism in the sports industry, attempting, like dark regimes, to unify all individual thoughts into one thought accepted by the ruler, thus creating a “beautiful harmony”—not in the school of the red fox.

To create a top athlete, quality is indeed necessary, but so is quantity. Therefore, it can be inferred through a simple transfer law that the top athletes of the future will be able to perform quality at a high quantity. 🙂

Why does much of the program include a lot of loss of control in the form of slides, falls, and rolls?

At the Red Fox, we have a saying, “the control within the lack of control”—meaning we actively seek a fundamental element of lack of control in our fast athletic movements, and we “ride” on it.

Just as a horse rider is measured by their “control” over the horse, which is external to them, an athlete is measured by their “control” over the lack of control, which in sports is divided into two parts.

- The art of responding to random stimuli over which the athlete has no control (for example, defense in soccer)

- Any biomechanical tactic that requires the active use of body weight for its success (such as sprint starts or changing direction).

In point 1, the “control within the lack of control” can be described by the ease with which the athlete responds to stimuli beyond their control, such as reacting to a teammate’s loss of the ball. On one hand, the athlete has no control over the mistake made by their teammate, but on the other hand, they must respond responsibly, technically, and gracefully to the lack of control that was previously created.

Any response generated from such a surprise situation will inevitably be “hurried” and lead the untrained athlete to panic mechanics and a freeze response, as is often observed on soccer fields. Therefore, we must insist that within all the changes of direction and random commands often seen in capability development training, the athlete uses controlled technique, grace, and not panic and lack of control. This requires a lot of grease, as the parts of the brain responsible for guiding the body get stuck in the complex gears of the random nature of the game, and as coaches, we need to grease them so they can perform effectively.

In point #2, we are talking about physical lack of control in the literal sense, as it manifests in the technique of sprint starts, changes of direction, or jumping.

For example, to sprint from 0 km/h and accelerate quickly, there is a need to leverage the body weight, including the direction of the push itself, towards a target that is not in the immediate vicinity of the body (like when trying to jump over a puddle, you must fully commit to target B, which is not target A, and any jump that is not intended to reach point B will lead to failure and getting wet). In other words, in the art of the first step, the one who aims for step B without being connected in any way to step A will succeed over the one who wants each step to be connected to the previous one due to fear of commitment.

הדבר לעתים מבטא עולם פנימי דומה, שבו יש לספורטאי פחד מ”לשחרר” את עברו ולהשות באוויר, בין 2 בניינים גבוהים -באמונה שהוא יצליח. נפש הספורטאי שכזה תסרב לנתק עצמו מהבניין הראשון שמא “יפול” ובכך מנציחה את הברוך שבו הוא חי, שמציג את הכמיהה שלו להתקדם לבניין השני אך באותו זמן את הפחד לנתק את בניין א’.

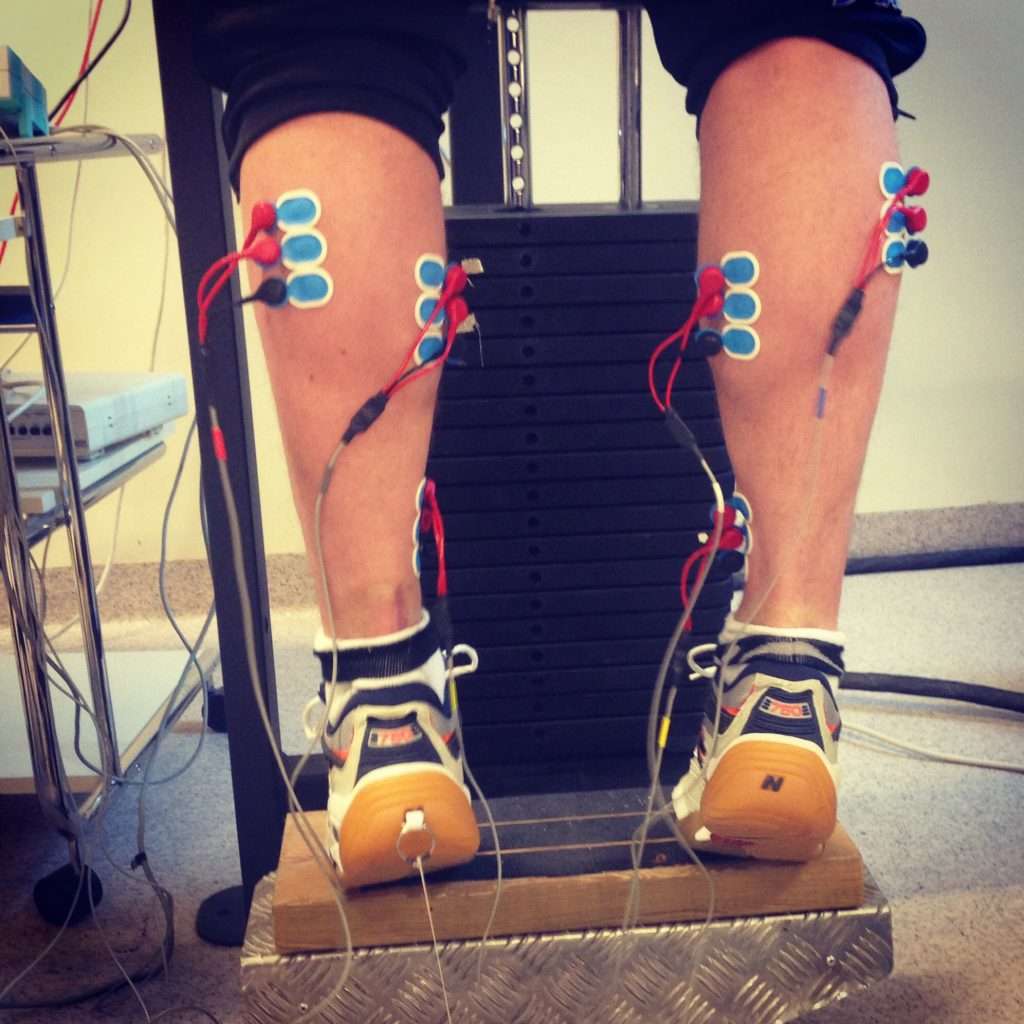

This is not, of course, a recommendation to jump over buildings 🙂 but rather a way to illustrate mentally the pain of breaking the chains of the past. Such a struggle can also manifest physically when training high-intensity athletic abilities, as seen in the images above.

Do “injury prevention reinforcements” play a central role in training?

“Did you do your prehab drills? Do them, it will prevent injuries for you.”

“Did you strengthen the gluteus medius? Strengthen it, it will prevent knee injuries.”

“Work on your groin and lower abdomen; it will prevent injuries in the groin and lower abdomen.”

Again, correct thinking but in the opposite direction 🙂 This is the same negative perspective on training that we saw with the issue of workloads—”Be careful not to overtrain.”

Why the constant focus on the negative micro aspects of which muscle is at risk of injury, which training is dangerous due to its volume, and which external rotation of the shoulder will prevent the next dislocation?

The painstaking work called injury rehabilitation and imparting the knowledge to return to past performance is the sole responsibility of the physiotherapist. Since when should fitness coaches waste half an hour of precious training time performing glute muscle activations and neural responsiveness in the form of footwork on a half-ball?

The role of a development coach is to instill the correct mechanics for each athlete individually, with the hope that this alone will bring about “passive injury prevention” that operates 24 hours a day simply by the fact that the athlete moves in sync with their ability and body form through the mechanics learned from their coach.

Active injury prevention in the form of isolating painful areas in the body is again a repulsive and negative effort that prevents the coach and the athlete from reaching new heights and keeps them in the “safe zone”—the ways of the past and the insurance policies that will keep you in Division B or Division A forever. The main thing is that you are “safe.”

We have often seen beginner athletes preoccupied with Kinesio tape and slow eccentric or isometric contractions in the gym on a regular basis, claiming they are “fighting injuries and acquiring insurance.” These athletes almost always end up injured, and to make matters worse, they are also significantly slower than “free” athletes who are not mentally bound to the world of orthopedics 24 hours a day.

It’s not that we don’t do an exercise here and there borrowed from our beloved physiotherapists’ dictionary, because we do! Especially during warm-ups or breaks.

But more in the spirit of things, we do not bandage an area we think might get injured because we are not negative people, and we believe that technique and movements are truth and, in themselves, reduce the risk of biomechanical injuries.

In fact, any athlete who comes to training at the Fox bandaged without a medical reason, whether with a bandage or “Kinesio tape,” is immediately required to release this defeatist behavior, remove the mental training wheels they created for themselves with bandages and armor, and meet the natural athletic world they are destined to master.

“But what if I get injured? I need the bandages” is exactly like saying, “But what if I fall?” when coming to ride a bike for the first time.